I. 3 Modern History of Greece

Anyone attempting to understand

something of the complexities of Greek/Turkish relations must come to grips

with the deep sense of loss felt for centuries by many Greeks over the fall of

Constantinople, (“The City”- now Istanbul) to the Turks in 1453.

Even after Greek

independence was formally recognized in 1830, various parts of

From an interview

conducted about ten years ago in

“My husband was

working at Pontos near

Also crucial to

an understanding of today’s Greek people, whether they be in Greece or in

Canada, is some brief account of the horrors which the Greek population

experienced during World War II and in the years of the Civil War from

1946-49. In both World

Wars Greece fought on the side of the western allies. In October 1940 the Italian Fascists under

Mussolini attacked

Here again are

the words of the same Greek widow, this time speaking about her own experiences

in

“It was during the German occupation in 1943 that I was walking barefooted from my village to the city hospital where my boy was being treated for polio. I was passing a German contingent when I heard shots. Some German soldier was shooting at the icon of Panayia [Mary]. I made the sign of the cross and called Panayia’s name. All of a sudden the soldier dropped dead on the ground. Whether he accidentally shot himself or someone else shot him, I don’t know. Also in the following Civil War, when neighbour turned against neighbour, the father of my daughter-in-law was shot. He was a good man and he had something wrong with one of his arms. Everybody who heard it was shocked that a physically handicapped man was shot and they all cursed the killer. Not long afterward the killer was cleaning his gun, when it went off and shot his arm, making him the same as his victim. We went through a lot of suffering during the Civil War. My husband, who was never interested in politics, was taken once and was beaten black and blue. When they brought him home, I was told that it was one of my next-door neighbours who had done it. What could I do, a poor woman, to save the father of my children? I went next door and instead of abusing him, I begged him to come and have dinner with us. When he came, I offered the best food that I had and he felt ashamed. That, however, saved my husband’s life. You could not contradict them, you had to coax them. This is the only thing I don’t like about the Greeks- when they turn against each other.”

Thus, it is easy

to understand that the years around 1950 were the time when hundreds of Greeks

who could get out, left their beloved homeland to seek new lives abroad,

particularly in

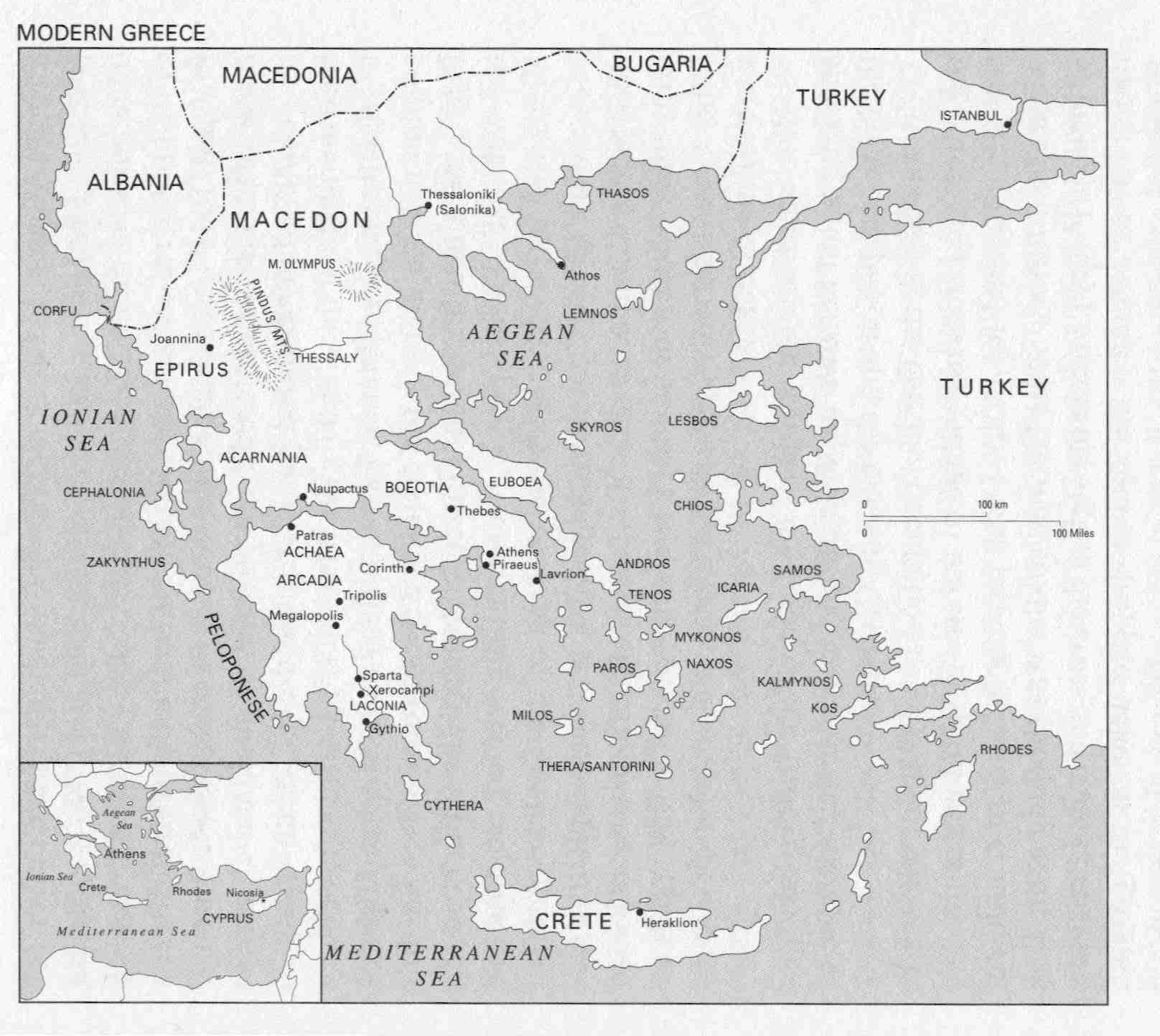

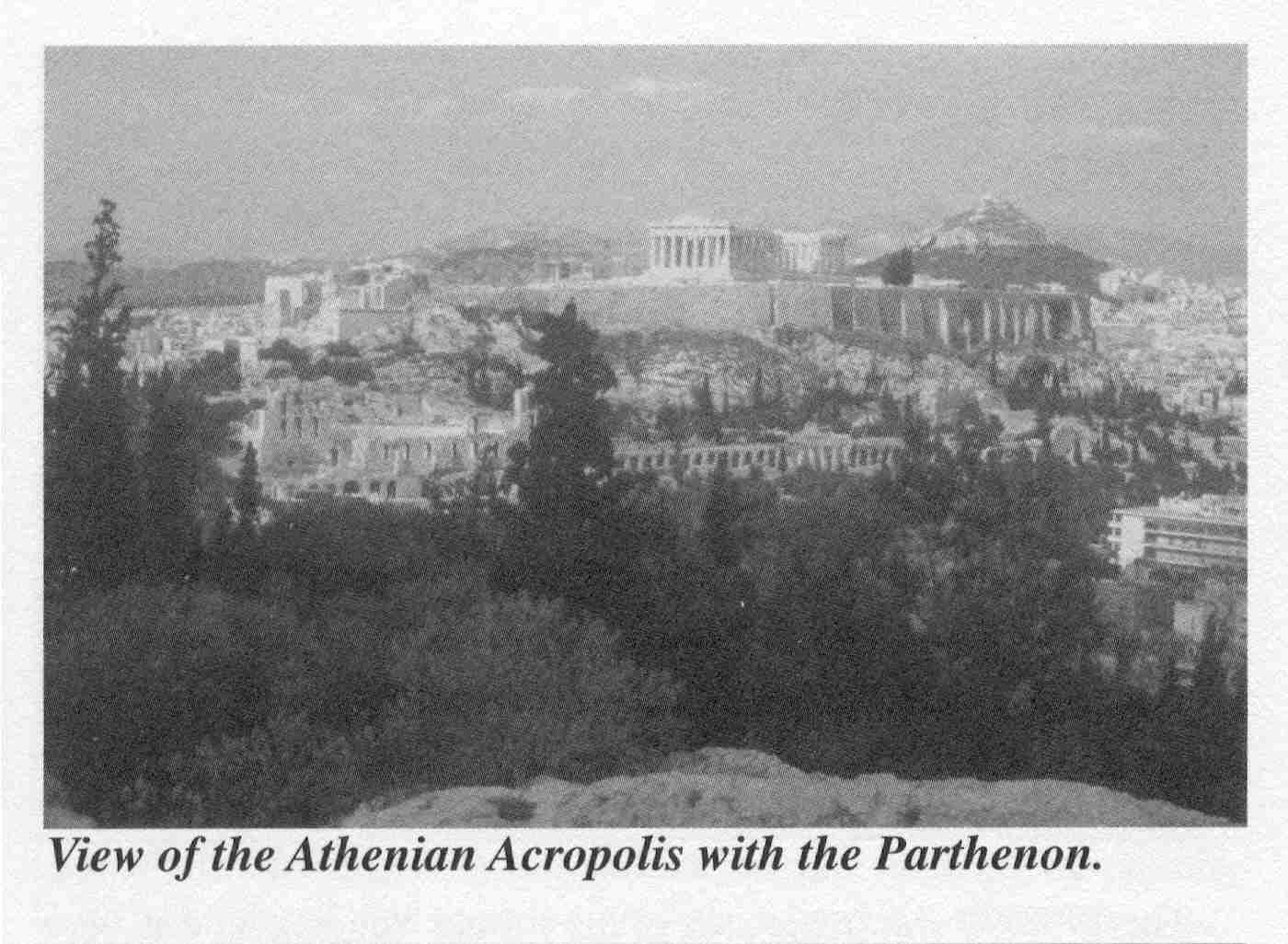

Slowly Greece’s economy is improving, with growth occurring primarily in the agricultural, manufacturing, tourism, and financial sectors. The years of poverty after World War II are clearly over. Throughout the country new buildings have sprung up, a wide variety of consumer goods is readily available, and children attend school as long as they and their parents want them to be there. Fine universities exist in places like Athens, Patras, Joannina, and Salonika, and there is a new university on the island of Crete. Many North Americans, both Greek and non-Greek, find modern Greece still to be a male dominated society, but that is quickly changing. Women in Greece have had the vote only since 1952. In the past the husband was in effect designated ‘family monarch’ and as such, he possessed the sole and ultimate right to decide on all household matters, including the right to direct the behaviour of all women in the household. A Family Law in 1982 officially changed all of that. According to this progressive law, all major household decisions are to be made jointly and children are to be under the care of both parents. The law officially abolished the dowry. Increasing numbers of women are now working outside the home and are to be found in all the major professions. Women such as internationally renowned singer Nana Mouskouri, the late actress and politician Melina

Merkouri, politician and former minister of culture Dora Bakogianni, and the

actress/theatrical producer Mimi Denissi, are household names in Greece. In the cities young men and women date and go around together as they do in North America.

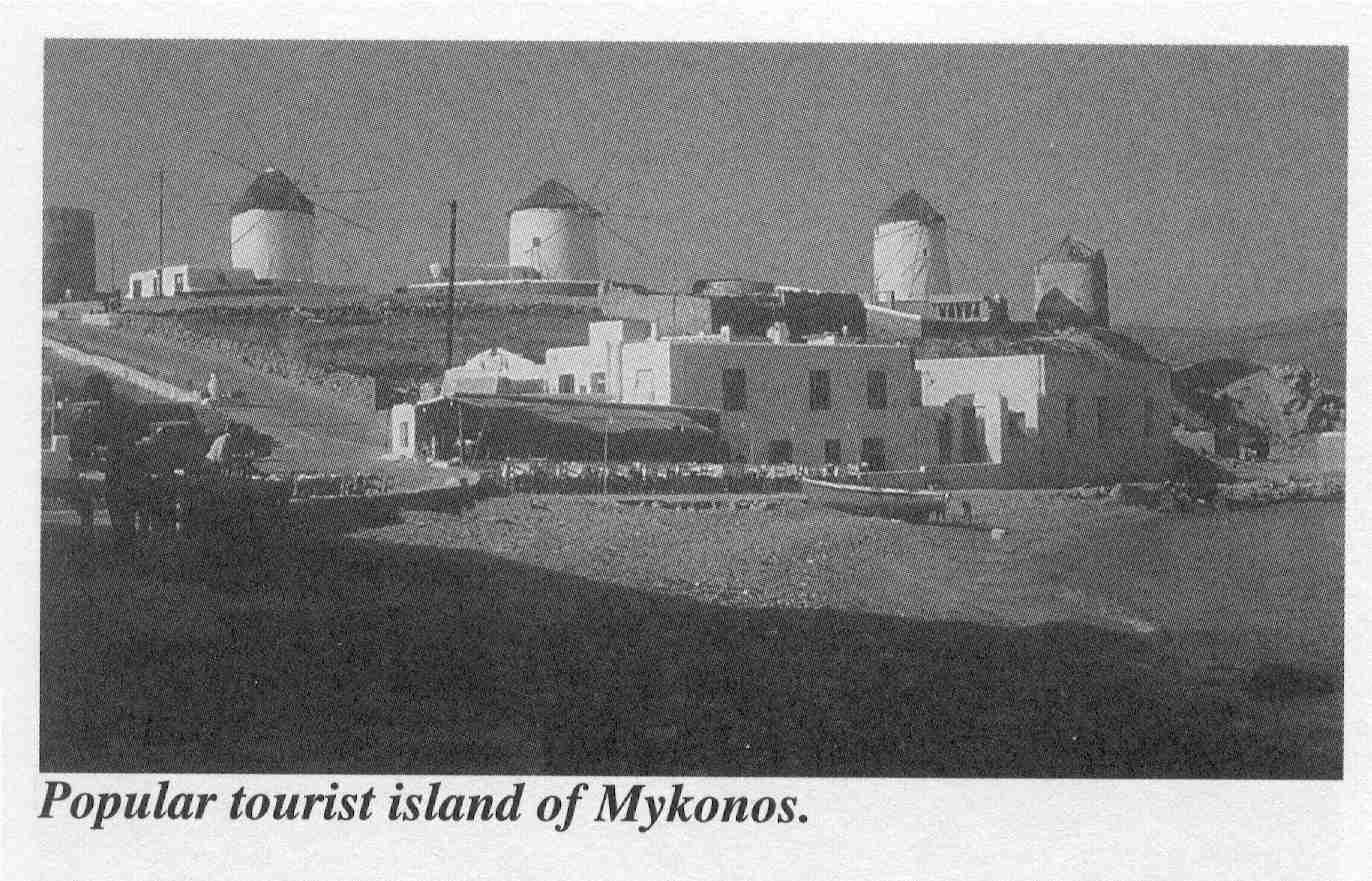

So many thousands of tourists visit Greece each year, particularly in the summer, that in many areas the beautiful stretches of pristine coastline are fast being taken over by a multitude of hotels, resorts, and restaurants. At the present time, one major economic problem in Greece is the persistence of a large public service deficit caused by an inefficient state sector and abuses in the tax and welfare systems. By 1995 new budgeting systems and grants from the European Union, (of which Greece is now a member), brought inflation under 10 % for the first time. Unemployment in certain areas of the country remains another serious problem, particularly among those with limited education and few job skills. Thousands of Greek migrant workers continue to live and work in Western Europe, most of them in Germany. From time to time these men (and almost all of them are men) return to Greece to try to rebuild their lives, rejoin their families, and seek employment with some of the skills they have acquired working abroad. Unfortunately, recent statistics show that many of them return to unemployment in Greece, or are forced to settle for unskilled or seasonal jobs.

The 1998-99 war in the area of the former Yugoslavia was very painful for Greece; tension about that conflict remains high. Not only is Greece near the combat zones, but, as a member of NATO, she is obliged to support NATO’s stand in favour of the Muslim Kosovars and Ethnic Albanians and against the Orthodox Christian Serbs. Greeks remember that the Serbs fought with them in support of the western allies in World War II, while the Albanians sided with the Germans and Italians. Thus, many Greeks find the policy of hostility against the Serbs and support for their opponents both unnatural and distasteful.

During the late summer of 1999 a terrible earthquake shook Turkey, the worst effects of which were experienced not far from the ancient city of Byzantium-Constantinople-Istanbul. The material damage was enormous, but much more tragic was the fact that thousands of people were killed, and even more thousands sustained terrible injuries. Recovery from that disaster will take years, and the human suffering for those affected will remain for decades. Although Greeks and Turks have often been at odds with each other over the centuries, when word of the disaster became known, the response of the Greek government and its people was immediate and generous. Greece sent money and supplies to the devastated areas, and Greek people worked shoulder to shoulder with the Turks and other international aid workers to try and save those trapped in fallen buildings. When another earthquake hit the Athens area in September 1999, the Turkish people immediately reciprocated by sending help to Greece. The world’s hope is that these two countries who have shared recent natural disasters, and been so generous in coming to one another’s aid, will in time be able to reconcile their long, troubled past.