II.2 Adjustment

to Life in Canada

The early Greek immigrants to the

Earlier immigrants

who had built up Greek restaurants and other small businesses provided jobs for

the newcomers. They often paid low

wages, but these earlier immigrants did provide housing, assist with strange

governmental regulations and local customs, and help with the sponsorship of

the newcomers’ relatives who had been left behind in

In both

As still more

Greek immigrants poured into the large American and Canadian cities, they formed “Greek towns”.

In essence these were ethnic ghettos where the Greek immigrants spent

the whole of their non-working lives. If

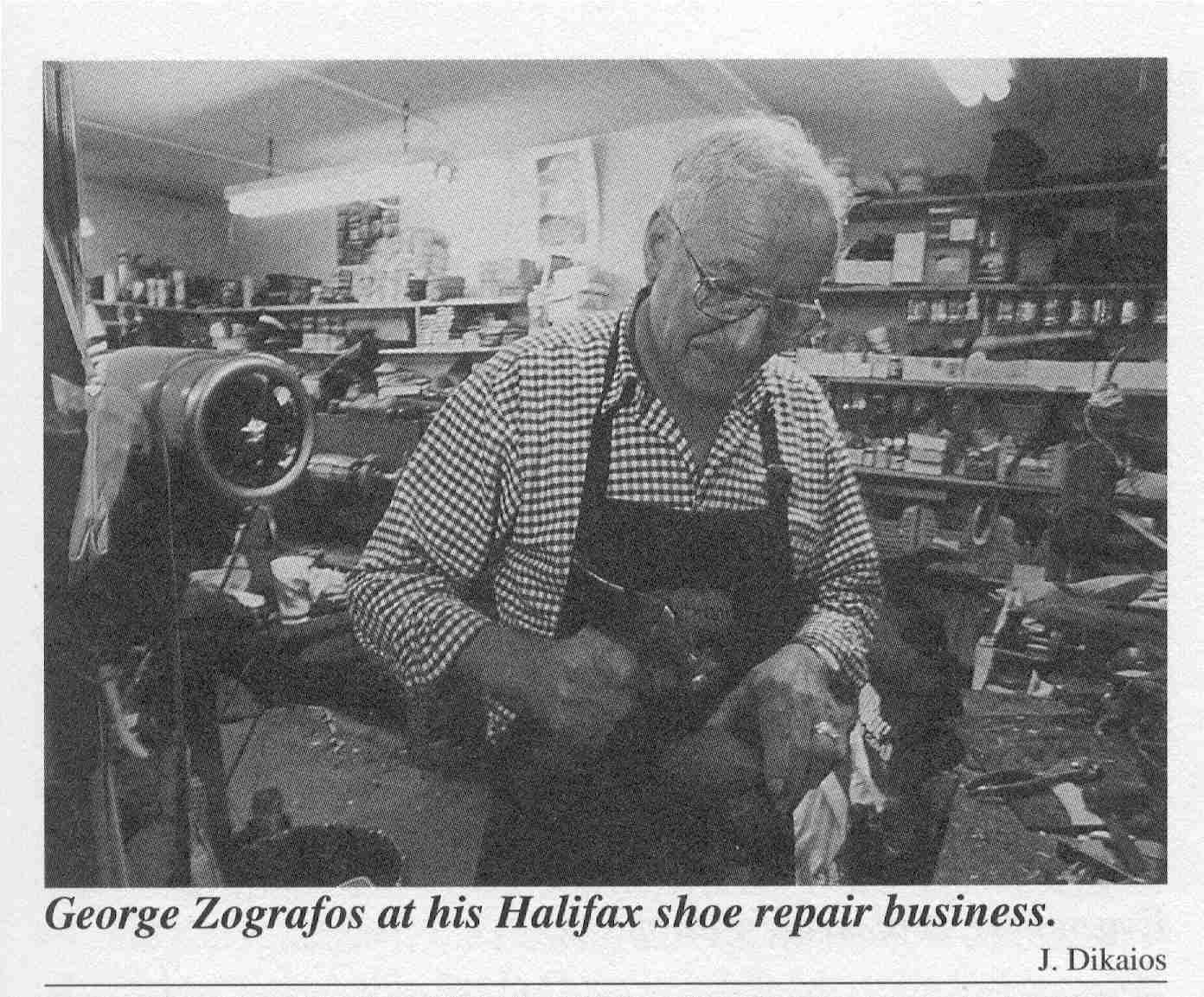

they were employed in, or owned one of the Greek restaurants, bakeries or shoe

repair shops, they also spent their working lives in those Greek enclaves

within the larger cities. The heart of

these communities was the kafenion,

a replica of the traditional Greek coffeehouse where men of a Greek village

talk and exchange news. In 1906 the

Greek immigrant men in

Gradually, the

immigrant men married and family life strengthened in

Since the

beginning of Greek immigration to

All large

communities in

One of the most striking aspects of Greek life in Canada is the fact that the majority (perhaps as high as 97% in the Toronto area) of the Greek immigrants came from semi literate and unskilled backgrounds, and they entered jobs which required few, if any skills. However, by the time of their retirement these same first-generation Greeks owned their own small businesses, or had moved into occupations which required considerable expertise. The restaurant business most of all was the Greek road to “upward mobility” and “economic achievement”. In the early years of the 20th century this particular business did not require much knowledge of English or French, and there were no formal educational requirement to produce good quality, basic food. Operating a successful restaurant demands long hours and constant hard work, but most Greeks were, and are, accepting of that. Many Greeks are naturally outgoing and their personalities fit the easy give and take of a neighbourhood restaurant. The restaurants also provide employment for many members of an extended Greek family.

During the years of World War II Greeks from across Canada supported the Allied war effort, lending special support to the Greek Relief Fund. That Fund raised large sums of money, and through the Red Cross went food, clothing, and medical supplies to those suffering in Greece. The Greek Relief Fund continued to operate and send help to Greece during the subsequent Civil War. In the years 1950-74 as Greek immigration to Canada peaked and then declined, most of the newcomers were busy arranging their own lives and those of their families. However, Greeks throughout Canada continued to follow the tumultuous turning of events in Greece. Some supported one group or faction, some another. During the military dictatorship in Greece, which lasted from 1967 until 1974, Andreas Papandreou, who had been a leading opponent of the regime, lived in Canada and taught Economics at the University of Toronto. Greek Canadians everywhere felt drawn to Papandreou’s Panhellenic Liberation Movement. After the fall of the military dictatorship Papandreou returned to Greece where he became Prime Minister of the country.

Now as we enter a new century and millennium Canada is home to second and third-generation Greeks. The young people are more interested in Canadian politics than in Greek politics. In the past Greek Canadians were not actively involved in Canadian politics, but that is gradually changing. In 1999 the Toronto area had at least five men of Greek descent serving as City Council members. Mrs. Eleni Bakopanos is currently a Federal Minister of Parliament (Liberal) from Montreal, and serves as Parliamentary Secretary for the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada. Mr. Jim Karygiannis is the Federal Liberal Member of Parliament for Scarborough-Agincourt in Ontario, while Mr. John Cannis, also a Federal Liberal, represents the nearby riding of Scarborough Central. Several Greek Canadians sit or have sat in provincial legislatures. For example, in 1999 Dr. Marie Bountrogianni was elected to the Ontario Legislature as a Liberal representative for the riding of Hamilton Mountain. In the 1998 provincial election in Nova Scotia Mr. Peter Delefes became the elected New Democratic Party member for Halifax Citadel, but in the change to a Progressive Conservative government in the July 1999 voting, he lost the seat..

The second and third-generation Greek Canadians are increasingly well educated. While their parents and grandparents may continue to feel that they are more Greek than Canadian, the younger people are comfortable being both Greek and Canadian. Through their parents and grandparents’ hard work and their own diligent efforts many are now active professional and business people. They have moved into education, law, medicine, engineering and a variety of other fields. Many of them own well established, flourishing businesses, some of which have been in their families for years. Construction and real estate projects seem particularly attractive, as some individuals and families let go of the restaurants and stores of the past. Of course, many Greek Canadians continue to own small or midsize restaurants as well as other traditional stores and service-oriented outlets. They are nearly always well run, and they provide personal, quality service. The work ethic exemplified by the early Greek immigrants to Canada is everywhere alive and well.