IV.

Society, Culture, Education, and Language

The Greek people of the Maritimes

are as diverse in their behavior and interests as any other group. Yet they have certain common traits which

tend to be particularly characteristic of them as Greek Canadians. Current (1996) statistics figures provided by

Statistics Canada show that 83% of all adult Greeks in this area are married, and that only 1.6% of them have had a divorce. While it is very much changing with a younger

generation, the Maritime Greeks always tended to prefer Greek Canadians or

Greeks from

In Maritime Greek homes family

strength and unity are all-important. We

often find that the married couple has a strong sense of partnership. Many husbands and wives have worked closely together for years in developing and sharing

the responsibility for a family business.

In those homes as the children grow into their teens, they often take

turns looking after the small diners, pizza places, or stores which their

parents own. Greek parents consider

their children (and almost every Maritime Greek family has children) to be the

centre of the home. When it is possible,

the family travels to

In the past, the mother of young

children normally stayed home, and children were rarely left with anyone

outside the immediate family. A few

years ago the author’s interviewers could not even find a word for

"babysitter" in the vocabulary of Canadian Greeks in

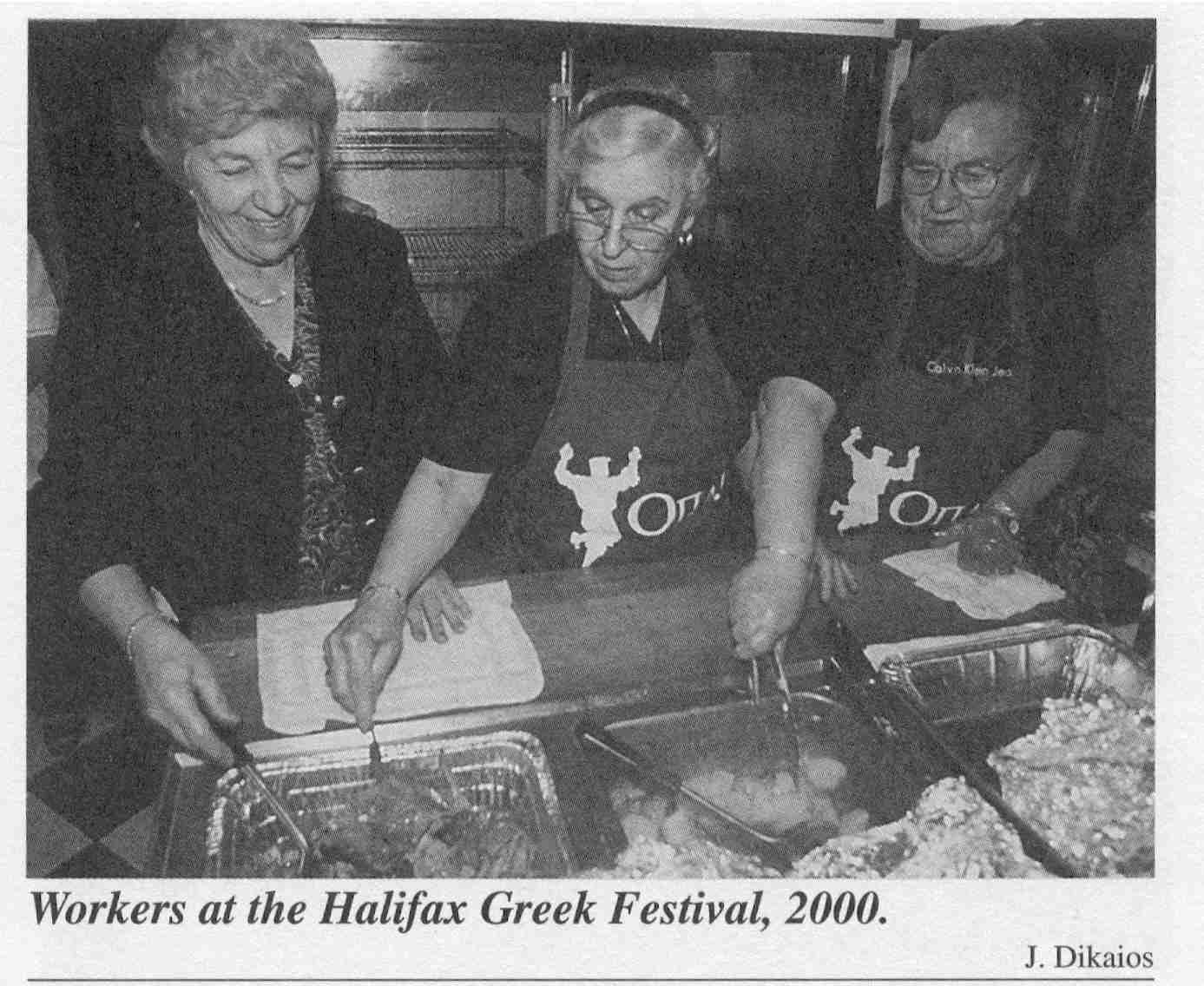

Most middle-aged and senior Greek women,

even if they work outside the home, take pride in cooking traditional Greek

food. Some of the Maritime Greek homes

have a grandmother or yiayia, who

lives with her married children, and does most of the traditional cooking. The children have learned to enjoy roast

lamb, moussaka (a sort of ground

meat and eggplant casserole), spanakopita

(spinach pie), and kourambiethes

(butter cookies). When the Greek Church or one of its organizations puts on a

social event or fundraising activity, the women of the Greek community are

called on to produce Greek food, sometimes in great quantities, for the event. Whether or not the women are directly

associated with the group requesting the food, or

whether they may themselves have major time commitments in other areas of their

lives, most inevitably and cheerfully comply with the request. One concern in the area of food preparation

is that some of the younger Greek women have not learned, or have not had the

time to do traditional Greek cooking.

The older women are sometimes quite protective of their recipes and

unwilling to share them with a younger generation. Some of the younger women in the community

are now beginning to realize that if they do not soon learn the preparation of

the traditional dishes, those skills will die out with the passing of the older

members of the community.

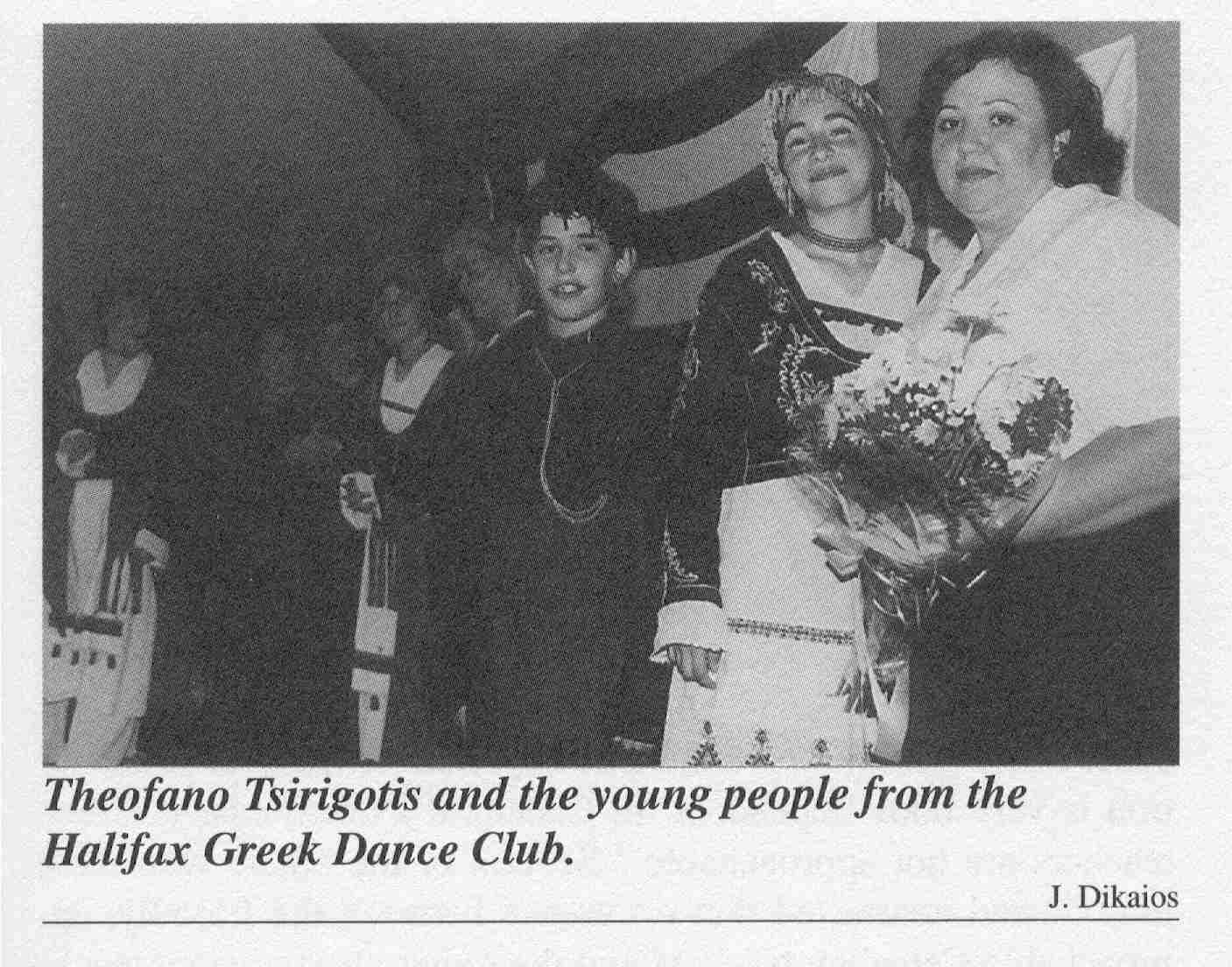

Also characteristic of most Maritime Greeks

is a strong interest and pride in their culture. I have already talked about the great

enthusiasm the young people in the Halifax area show in learning and performing

the traditional dances from Greece.

Teens and adults alike also want to learn something about the glories

and struggles of their Greek past. At local universities such as Dalhousie and

Saint Mary's professors who offer courses in Greek History, Mythology, and

Ancient Art regularly find that they have one, two, or more students of Greek

background in their classes. In the

Halifax area it is common for leaders of the Greek Church or for individuals in

the Greek community to invite guest speakers to come and talk about the history

and culture of both ancient and modern Greece.

Many Greek homes contain pictures and artifacts from Greece. Brightly woven fabrics, copies of Greek

museum pieces, and antique brass dishes hold pride of place as home

decorations.

Today most Greek families in the

Maritimes prefer not to live too close to one another. Some are quite adamant that they do not want

to live in any sort of Greek enclave, and have told interviewers that "we

will move if any other Greeks move into this neighborhood." In Halifax with increased prosperity many

have moved out of the older parts of the city and now live in the west or

central parts of town. Some families are moving outside the peninsula to

recently-developed areas in Dartmouth, Clayton Park, and the Purcell's Cove

Road area where the new St. George's Church is located.

While in large Greek cities there is

much socializing and interaction between men and women in the cafes, dance

halls, and restaurants, in the villages men still congregate daily at the local

coffee shop or kafenion to smoke, snack, and catch up on all the local

gossip. Women are almost unknown in such

establishments. As we have seen, early

on the kafenion became a regular part of daily life for Greek men in North America. A very modified version of the kafenion

environment exists in the Maritimes today.

It is not unusual to see local Greek businessmen in Halifax visiting one

another's stores and restaurants during the day, and stopping for a chat and a

coffee. Other Halifax men of Greek descent spend time at The Club in the city's

downtown where they can relax, shoot some pool, and have a drink in a primarily

male environment. Greek men in Saint

John regularly drop in at the popular Vito’s Restaurant for a coffee or lunch

together.

While there are certainly

exceptions, many of the immigrants who came to the Maritimes after the First or

Second World War had very limited formal education. They had left behind a war-torn,

poverty-stricken Greece where in rural areas school ended at the sixth grade. Of 109 Maritime Greek women interviewed in

the 1980s, two (1.8%) had never been to school, thirty (28%) had an elementary

school education, three (2.8%) went as far as junior high, forty-three (39.5%)

had partial or complete high school, and thirty-one (28.4%) had been to

university. At the time of the

interviews most of the women who had completed high school or been to

university were under forty, or were from the few families who had emigrated

before World War II and had been educated in Canada. Many of those women who came to Canada from

Greece before 1955 never acquired much fluency in English. They arrived with little or no skill in the

language and they had few contacts outside the family and Greek social

circle. While their husbands did learn

enough basic English to survive in their shops and small business, the women

generally did not. Mrs. Katina Manos of

New Glasgow who died at 89 in 1991 is typical of the older generation. She and her husband had come to the New

Glasgow area of Nova Scotia in the 1920s.

Some years ago in an interview conducted in Greek she explained that in

her small village near Sparta she had never had the opportunity to go to

school. Her poignant words were "it

was more important to keep alive."

Mrs. Manos had six children educated

in Nova Scotia. The girls'

education ended at junior high school, but her two youngest children, both

sons, went on to complete university.

One son, Dr. James Manos, is now a university professor and the other,

George Manos, was principal of a school and now is a county councillor in New

Glasgow. All of Mrs. Manos' elder

grandchildren are now studying in university, and James Manos’ two daughters,

Daria and Sarah, are both in medical school.

As the older generation of monolingual Greek speakers gradually slips

away, so too do the problems of living in a language, culture, and educational

environment different from the life which they had left in Greece.

Greek families of the Maritimes

today are characterized by a fierce determination to educate their children in

as broad a range of subjects as possible.

Several Greek families in the Maritimes send their children to French

immersion programs where these programs are available. These children learn French as well as

English in day school, and then learn Greek at home and in Greek school at

night. Older Greeks who themselves faced difficulties in receiving an

adequate education in Greece are determined that their children and

grandchildren shall stay in school as long as possible. The parents are willing to make real personal

sacrifices in order to provide for their children's education and ensure a life

of opportunity. Because of their

parents' support, few Greek Canadian young people need to take out student

loans. Today many young Greek Canadians

in the Maritimes have entered and successfully completed undergraduate and

graduate degree programs in a variety of fields. They are becoming established as medical

doctors, lawyers, engineers, accountants, successful business people and

educators. In the Maritime Greek

community young and old alike see education as the key to future success.

IV.3

Preservation of the Greek Language

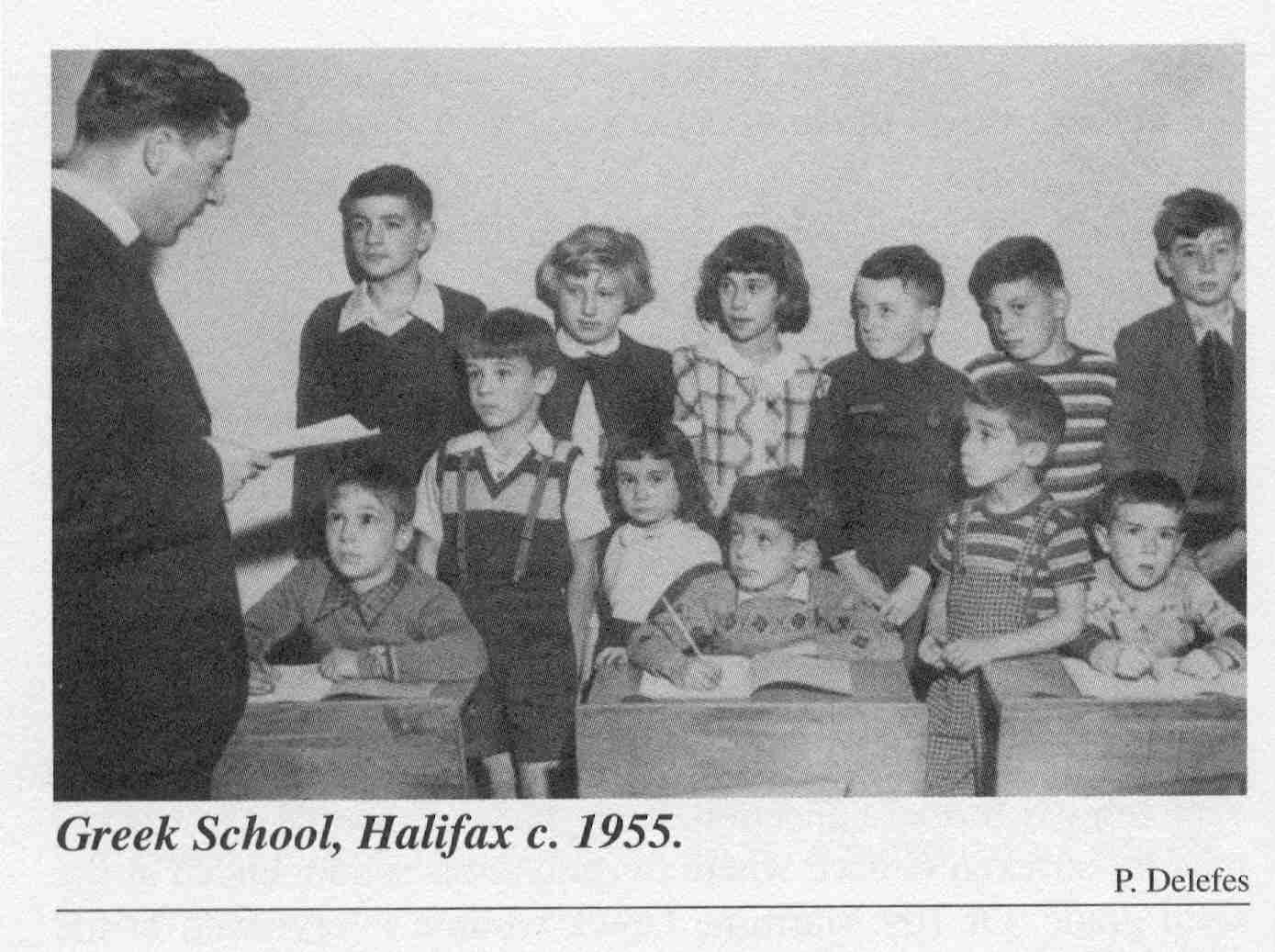

The determination to preserve the Greek

language in North America and pass it on to the next generation is one of the

most important cultural goals of North American Greeks. Many Maritime Greeks keep the Greek language

alive by speaking it at home and by frequent travel to Greece. The priest at St. Nicholas’ Church in Saint

John points out that many Greek Canadian families have grandparents living with

them, and that is the primary way through which the children gain regular

exposure to the Greek language. He himself talks in Greek to the children as

much as he can, both informally, and as their teacher in the Saint John Greek

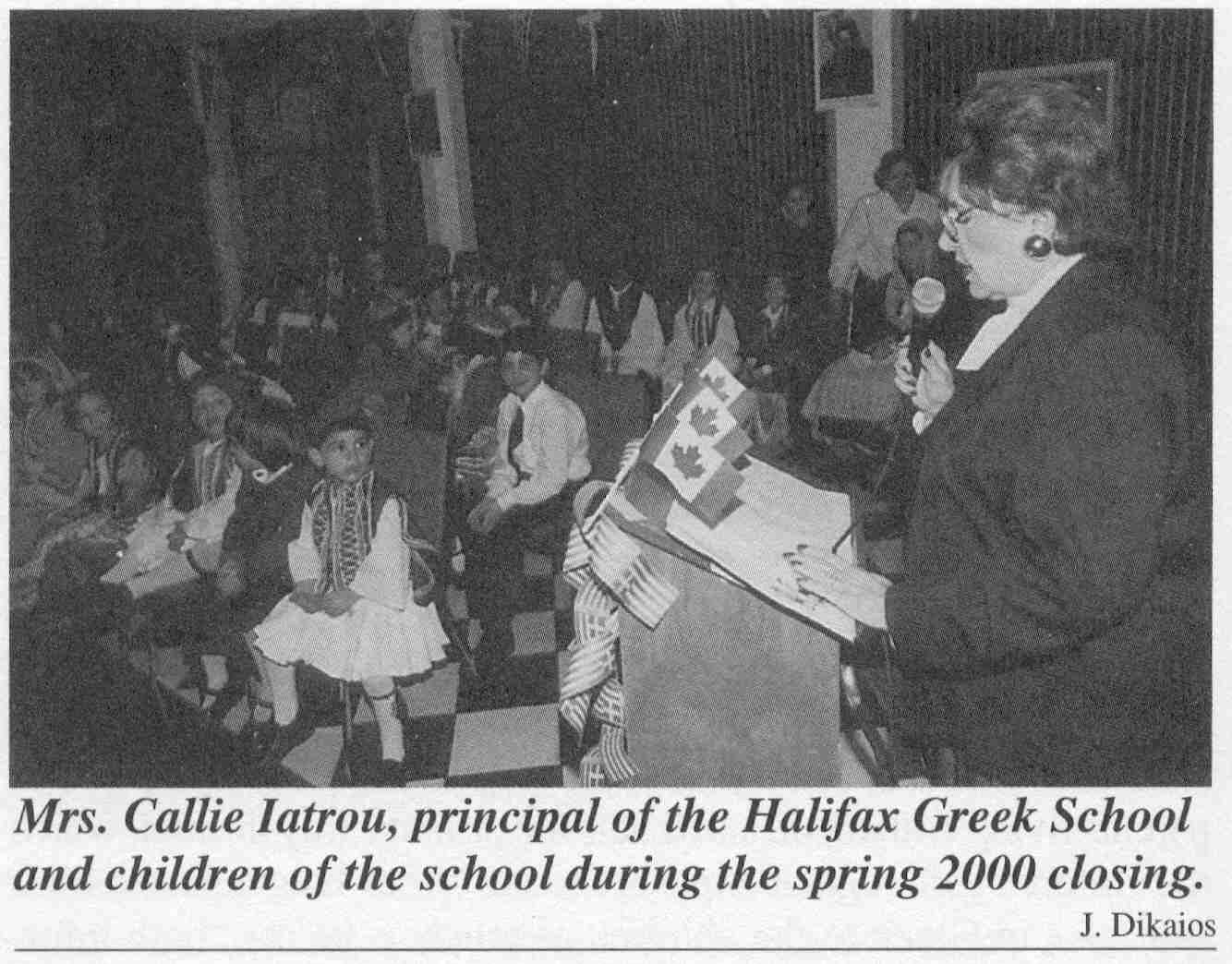

School. Greek schools have been in North America since 1931 and in Halifax

since the 1950s. According to the

principal, Callie Iatrou, the Greek School in Halifax, which goes from grades

one to six, and employs two teachers, presently enrolls about 60 children. That number is down from the high enrollment

days of the 1970s and 80s when the school contained over 150 students. However, a recent increase in the number of

Greek babies in the community suggests that the number of children for the

school will rise again within the next couple of years.

Since the Halifax Greek School

operates as a twice weekly, evening program after the regular school day, it

puts pressure on both students and parents alike. Funding for the teachers' salaries comes from

a fee paid by participating families, fundraising activities organized by the

school board, and donations of the Church Council. The Greek government, which supplies a large

number of books for the different grades, also provides accreditation for the

school. In theory that means that a

pupil who completes a particular grade in the Halifax Greek School could pass

into the next sequential grade if that child's family moved to Greece. However, given life in a Canadian context, where

the children are surrounded by the English language in their daily lives, it is

very difficult to make a smooth transition from schooling in Canada to that in

Greece. According to Mrs. Iatrou, many

children attending the Greek school in Halifax now come from homes where Greek

is not spoken as frequently as in the homes of earlier generations of Greeks in

the Maritimes. Thus it is a struggle for

the school to maintain the same standards of spoken and written competence in

the Greek language as in the past.

Anyone who wants to learn to read and

write Greek has to learn not only a new vocabulary and new, often complicated

grammatical forms, but also a completely different alphabet. That alphabet of twenty-four letters does not

correspond exactly with the western or Latin alphabet, as there are, for

example, two different "o" vowels. What sounds like "e" to

an English trained ear can have a number of spelling possibilities in

Greek. In addition, some of the capital

letters look very different from the forms used for the lower case

letters. Increasingly, Greek schools

rely on books published in North America rather than in Greece, because the

North American materials use a teaching/learning style likely to be more

familiar to children educated in Canadian schools.

Along with education in the Greek

language comes a strong measure of Greek religion, traditions, mythology, and

history. For Christmas and at the end of

the school year the children give public presentations of poems, songs, and

plays. The Greek schools also foster a

strong feeling of pride for the Greek homeland, one that is founded on the

glories of ancient and modern Greece.

Days such as March 25 or October 28

are of special importance for all Greeks, as they remember their

ancestors' struggle for independence from the Turkish and Italian rulers of the

past. On those days children in the

Halifax Greek School present patriotic poems which they have memorized, put on

plays, and perform traditional Greek folk dances. The dancing itself is a regular, weekly part

of the Halifax Greek School's activities in addition to the more academic

studies.

In the past St. George's in Halifax

has also run Greek language classes for interested adults, but in recent years

such language classes have become available outside the church through Saint

Mary's University. Prof. Niki Hare, who

is a Greek Canadian born in Cyprus, gives these classes. Adult learners of Greek tend to be those with

a strong interest in Greek culture, and a fondness for Greece itself. Some students are not Greek by background.

Others are Greek Canadians who wish to improve their Greek, especially their

reading and skills. Still other adult

students have married local Greeks and wish to feel closer to their spouses'

proud cultural and linguistic heritage.

IV.4

Stories, Customs, and Traditions

In each society and ethnic community

there exist stories, customs, and traditions which add unique features and

color to the life of the people. Since

the time of ancient Greece the making of stories and particularly the creation

of myths have been characteristic of the Greek people.

This first story is from a Halifax

Greek lady whose family comes from the village of Xerokampi, near Sparta in

southern Greece. Here are her own words:

"My mother told me a very

moving story about St. Nikonas where an interesting custom about the baking of

the church bread (prosforo) is

revealed. St. Nikonas was a well-known

saint around the Peloponnese, because he was supposed to have visited it after walking across the Aegean Sea from Asia

Minor. He preached in the Peloponnese

and died there, but nobody knew the place where he had been buried. One night a little boy, bearing the saint's

name, had a dream in which the saint revealed to him where his bones lay. When the little boy told his mother, she was

first frightened and did not say anything.

Finally she told the priest who summoned the whole village of Xerokampi

into a meeting. They all took their

shovels and started digging until they found the holy bones. Then they transferred the bones to Sparta

where they built a magnificent cathedral bearing St. Nikonas' name.

All the villagers took home with

them a little bit of the earth that held the saint's bones. My mother's aunt took some, and when she baked the bread to take to the

church for her husband's mnemosyno

or anniversary service for his death, she put a tiny bit of the earth in the

dough. She made two round loaves and stamped

them, but one of them looked cracked.

That one she gave to a poor man and the other she took to church. When she went to sleep the next night, she

dreamed that her husband was thanking her profusely for the great gift which

she had sent him. She was surprised for

she didn't think that she had done anything special. In her dream her husband pointed at the

cracked loaf, which he was holding in his hand.

That loaf was the one which she had given away. Her husband was pointing at a tiny piece of bone,

St. Nikonas' bone, in the loaf. St.

Nikonas' feast day is the 26th of November."

The Greek people of the Maritimes

have brought with them customs and traditions that are important to them as

individuals, as families, and as members of a community. In this book customs are defined as practices which are done over and over again

by individuals and by families. These

customs may only exist across the life of one person or one family, or they may

have lived in a particular family for a number of generations. While some Greek families in the Maritimes

have customs similar to those in other families, there are often real

differences among families. Traditions are defined as ways of doing things, which are often

hundreds of years old and are held in common by a great number of people. Even within common customs and traditions

certain modifications can be found from one family to another and one region to

another.. Described below are some

customs and traditions which the Greek people of the Maritimes have remembered

and brought, sometimes in a modified form, from Greece. Expect to discover slight variations as

people from different parts of Greece tell their stories.

A wedding always demands special

ways of doing things to help make the occasion memorable. Anyone planning a wedding begins to consider

styles of clothing, types of food, the nature of the ceremony, and the use of

special, old customs which make us laugh, but also are maintained because

‘that's the way it always is at weddings’.

Most of us are familiar with wedding customs such as the garter, which

the bride wears on her leg and the new groom removes. We throw confetti or rice at weddings, and at

the reception’s end the new bride throws away her bouquet.

Greek people often do these things

too, but they also have special Greek customs and traditions for weddings. Mrs. Pota Kouyas of Stellarton whose family

comes from a village in Laconia in the southern Peloponnese, told an

interviewer that it was her family's custom to give a bride and groom each a

spoonful of honey to eat in order to sweeten their marriage and their married

life together. She also said that

friends of the newlyweds place a horseshoe on the threshold of their new home,

and that the bride and groom each step on it as they enter. This brings good luck to the marriage. Mrs. Sophronia Georgakakos of Halifax, whose

family also came originally from the southern Peloponnese, but from another

village, added her versions of these wedding customs. Mrs. Georgakakos said, "When the

marriage ceremony in my part of Greece is over and the bride and groom go home,

they find that the bridegroom's family has placed a steel bar at the entrance

to the house and on the top of the door so that the couple will have a strong marriage. The bridegroom's family also makes up a cross

with honey so the bride will be ‘sweet’ for her new husband."

Mrs. Bessie Katsepontes who is from

the village of Palaiopanayia, also near Sparta, gave us her version of the

‘sweet’ wedding stories. She said,

"In our village before the wedding young village girls- and they must be

unmarried girls- come to decorate the new couple's bed and room with sweets-

usually almonds- which they hide in the new sheets. Sometimes they play small tricks on the

couple with the funny things they hide in their bedroom. After the church wedding when they are back

in the groom's home, his mother gives the new bride honey in a silver

spoon. After the bride has eaten the

honey, she throws the spoon behind her.

Whoever catches the spoon can take it home as a souvenir."

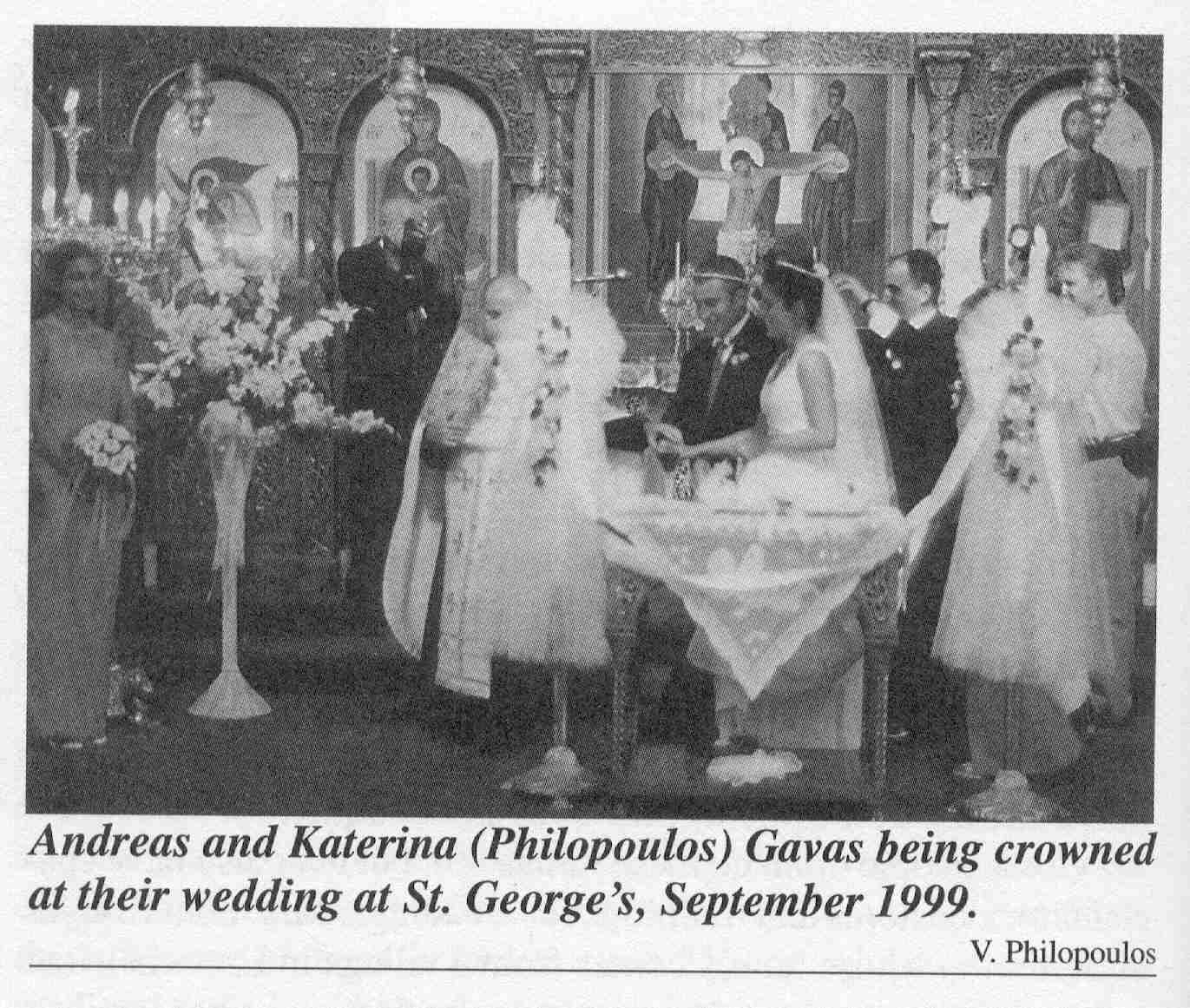

Greek weddings in the Orthodox

Church have several features, which are both colorful and traditional. First, the principal, official sponsors or

attendants of the new couple, the koumbaros

(male) and koumbara (female), must

be Orthodox and in good standing with the Church. They may be relatives of the young couple,

but need not be. Even if not related,

the koumbaroi (plural) are treated

almost like family, and often will be asked to be the godparents of the new

couple's first child. In the wedding

itself the crowning of the bride and groom is the climax of the service. Before the wedding the

priest has

placed a tray holding two crowns on a small table at the front of the

church. The stephana or crowns of fresh or artificial flowers are joined by a

single ribbon and signify the glory and honour with which God is crowning the

couple. The church teaches that on earth

they are being crowned as the king and queen of their own little kingdom, which

they will rule with wisdom, justice and integrity. When the crowning begins, the priest takes

the crowns and holds them above the couple saying,

“The servants of God

(name) and (name) are crowned

in the name of the

Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

The koumbaros and koumbara then

simultaneously switch the crowns three times above the heads of the bride and

groom to demonstrate that they are being crowned in equality, dignity, and mutual

love and support. Usually the crowns are

preserved carefully at home on a stand or in a special case close to the

marriage bed, and preferably they are never touched or disturbed, to avoid the

possibility that the marriage itself might be disturbed. Near the end of the wedding service, the

priest leads the bride and groom in a circle or dance around the table on which

are placed the Bible and the Cross. The

walk or dance is always done in great joy- the joy the couple have the right to

expect in their married life and the joy of beginning a new home with the

Christian faith and the Orthodox Church at the centre of their life together.

In Maritime Greek homes January 1st,

St. Basil’s special day, brings some of the most popular traditions which have

been transferred from Greece to Canada.

Mrs. Antonia Xidos, whose family comes from the island of Milos, told us

that early on January 1st her youngest son, Dino, appears at the doors of the

various family members, bringing with him rocks he has picked up on the

seashore. She said: “He places a rock

for luck and so the coming year will be strong like the rock under the bed of

the husband and wife in the home.” Mrs. Xidos’ married daughter, Cathy

Mavrogiannis, laughingly admits that she now has a collection of rocks from

numerous years under her bed. Her mother

says that it is all right to replace last year’s rock with this year’s

‘present’, but Cathy is not taking any chances!

Each household bakes its own Vasilopita

(cake or bread for St. Basil) to mark the beginning of another year. Everyone hopes to get a lucky coin baked

inside the cake or pita.

The Vasilopita commemorates a miracle

performed by St. Basil while he was a bishop.

The legend varies as to how St. Basil became the guardian of the gold,

silver, and jewelry of the people of Caesarea in Asia Minor. Some sources say that thieves had taken the

valuables from the village and that they were recovered. Other sources say that the treasures had

first been required as a tax by a hostile, pagan Roman governor, but that he

was so impressed by St. Basil that he returned the people's treasure to this

good man. In either case St. Basil was

supposed to return the treasures to the owners.

However, the villagers could not agree on who owned each particular

valuable piece. St. Basil suggested that

the women should bake the valuables inside a large cake or pita. When St. Basil cut the pita, each owner

miraculously received his or her own treasure.

Today a single coin is baked inside each loaf to honour St. Basil's

miracle, and the one who gets the coins is supposed to receive good luck for

the coming year. Greek people cut the

first piece of the Vasilopita at midnight on New Year's Eve. The head of the

household first says a blessing and then cuts the cake into pieces in a

specific order which remembers Christ and the saints, as well as family and

friends gathered at the table. In Greece

(and we suspect in some Greek Canadian households), a little Vasilopita and

some other food may be left out for St. Basil on his name day, January

1st. Anastasia Botas of Halifax told us

that in her home they don't receive presents on Christmas Day, but the presents

do appear with Saint Basil at New Year's.

Like weddings, deaths and funerals

attract patterns of traditional behaviour, which can be very tenacious. Several of our Maritime Greeks have told us

about death rituals from the southern Peloponnese in which the mourners,

usually the local women, create elaborate songs and poems (moirologia) to chant and sing beside the body of the dead

person. The family of Mrs. Chrysoulla

Raptis of Sydney came from Gythio south of Sparta. Mrs. Raptis said, "When my father died,

all the mirrors were covered with black ribbons. When someone has died, the people sit up all

night around the body. After someone is

dead and has been buried for three or four years, they take up the bones and

wash them with wine, put them in a box, and keep them in the church. When the family and friends go to the

'opening up’ ceremony, they say 'we're going to free so and so'. That means the earth somehow keeps the spirit

enslaved, and when the bones are out, the spirit feels free. When we were children, we were terrified to

go near that room full of bones at the church.”

While we in North America may find the

whole idea of the 'opening up' ceremony more than slightly macabre, it should

be understood, at least in part, as a practical way to avoid the expansion of

cemeteries. With this custom the family

tomb is available when the next member of the family dies, and the remains of

the one who has died previously are dealt with in a way that tradition and

church consider acceptable.

Because it is a different cultural

climate, and because Canada has stringent regulations about the disposal of

dead bodies, the practice of the ‘opening up’ ceremony does not exist in

Canada. However, Greek families do use

other rituals around death which are hallowed by their traditions, and which

help them deal with the terrible finality of losing a loved one. In some families it is still common for the

women to adopt total or almost total black in their clothing for a period up to

one year after the death of a close family member. Some women who are widowed may never remove

that black clothing. They are not

required by any church or community regulations to dress in this way. In fact, in some situations other members of

a woman's own family may find the totality of the black grim and hard to

endure, and ask for its removal. But

those women themselves feel comforted by their black attire; they feel that

they want to indicate to the world the grief that is within their hearts. Who, then, should look askance at their

dress?

The Greek memorial service or mnemosyno which occurs forty days after

the death of a relative, and special days of remembrance for the dead

throughout the church year are other ways through which Canadian Greeks deal

with feelings of bereavement. On those

remembrance days the women prepare, bring to the church, and share with friends

and family a traditional memorial dish called kolliva. This is made of

boiled wheat mixed with sugar, pomegranate seeds, and spices. The kolliva is a symbolic message of

everlasting life and hope. For Greek

Christians it is rooted in the words of St. John’s Gospel 12:24 where it says,

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and

dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” If one is asked

to share a taste of kolliva with a Greek friend, it is a mark of real caring

and expectation that we will understand what is being offered. It means that we participate with our friend

in remembering his or her loss, and we also remember our own dead with

affection and continuing love.